How Jack’s Decentralized Plan Could Save Social Media From Itself

Jack Dorsey is known for revolutionary, and sometimes controversial, ideas. As the CEO of two of Silicon Valley’s most powerful companies (Twitter and Square), what he says carries a lot of weight, so when he shares those ideas online people take notice.

Most recently, @Jack published a multi-tweet thread that outlined his plans to launch project Bluesky — an independent team of programmers and engineers who would be tasked with creating a new decentralized standard for social media.

Twitter is funding a small independent team of up to five open source architects, engineers, and designers to develop an open and decentralized standard for social media. The goal is for Twitter to ultimately be a client of this standard. 🧵

— jack 🌍🌏🌎 (@jack) December 11, 2019

The fundamental idea is that, rather than each social media channel being a closed system, there should be a universal standard that all social media networks would adhere to. That would allow third parties to build on them, developing new ideas and platforms. The idea is similar to the way that both Facebook and Twitter each allowed third-party developers to build apps and integrations on their platforms before shutting the gates when they began to lose control.

The benefit would be that a decentralized standard could create choice and competition, and it may even help to combat the common-source fallacy that causes so many of the current problems on social media right now.

Since the middle of the last century, our news has come from a few common sources – the media networks had combined and controlled our TV, newspaper, and radio channels. The result was that they were able to fund world-class reporting, distribution scaled efficiently, and we were all working from (roughly) the same set of facts. The most important job in media was uncovering those facts, investigating what was most important, and presenting them to the world clearly and without bias.

The idea that news was ubiquitous, that we were all getting our information from a common source, became ingrained in us to the point that no one noticed it anymore. “Did you see the news?” was a normal question that implied that the news was universal.

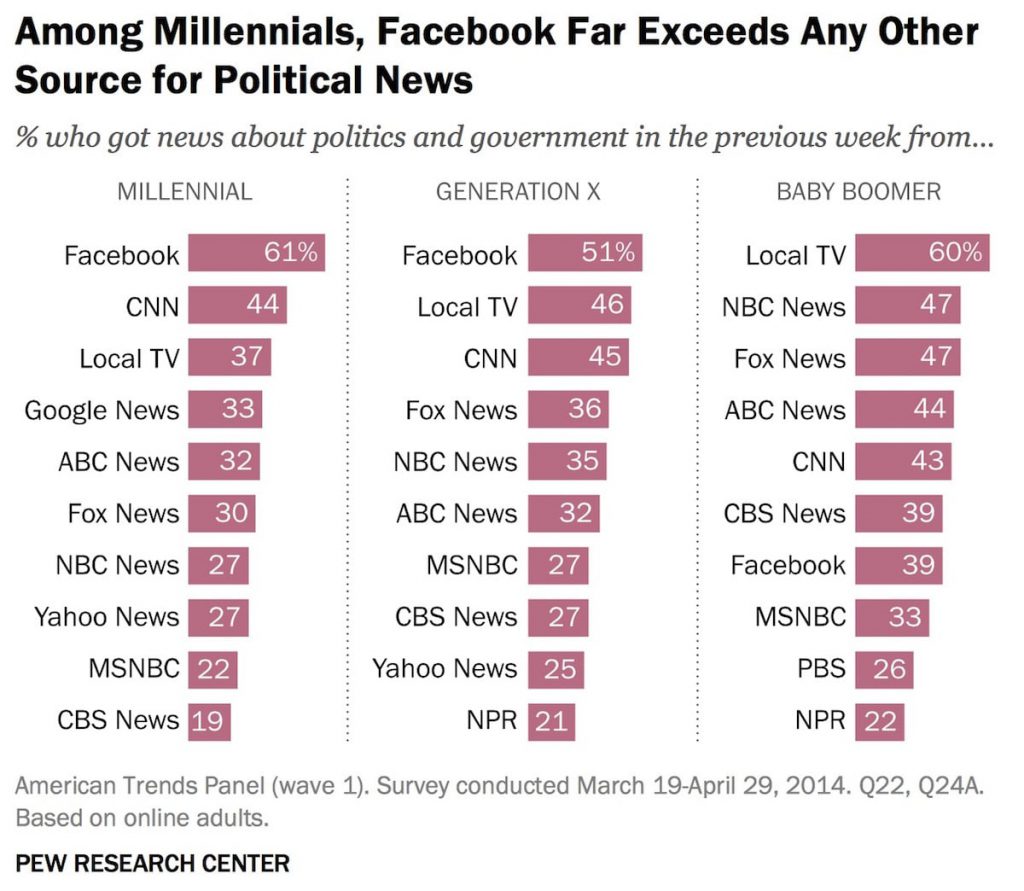

In 2015 everything changed. That’s the first year that Facebook became the most popular source of news for people in North America. The fact that we were collecting our information from a wider set of sources and exposing ourselves to new ideas seemed to be a good thing. The problem was that we hadn’t built up the necessary skills handle it, but the networks’ incentive was to convince us that we had.

Where previously we could take headlines at face value and our role in the news was only to consume, gathering news also meant investigating the source, evaluating its bias, and determining its truthfulness for ourselves. That takes a lot of extra effort, and entire generations never had to develop that muscle, so it just didn’t get used.

That lack of critical reading, coupled with the rampant spread of just a few social media networks, led to the segmentation that we’re seeing now – where pockets of people cluster together, adamantly convinced that their truth is the only one that’s right. Each group is appalled that the others don’t agree with their set of facts and, since the truth is so obvious to them, they write off the other groups as either having ulterior motives, being gullible, or just unreliable.

What’s interesting about the segments is that each one is trusting, to varying degrees, the same sources for the information that’s fuelling their beliefs. Climate change advocates see Greta Thunberg’s heroics across Facebook and Instagram, while deniers see articles on those same platforms that confirm that she’s a bought-and-paid-for propagandist. Republicans are faced with mountains of evidence that the 2016 election was rigged. So are the Democrats, but the motivations behind the rigging are presented to be very different.

As much as the common-source fallacy has damaged our understanding of news and politics, it’s also been the reason that so many brands have been so successful using social media and social advertising to change people’s minds. If people believe that their Facebook/Twitter/Instagram news feed is as reliable and unbiased as the Associated Press, then a message about a new product that they see show up from multiple sources must carry that same level of trust. This is especially true for people who grew up at a time when the world had limited media and brand options.

Does that make us wrong as brands that have been using digital as a marketing tool? Only if we’ve been intentionally misleading people. The power of segmentation has actually forced us to connect more deeply with communities, to create content that’s valuable to specific users, and to work with the people who are influential within those groups. All of those things have positive impacts, both for the user and for the brand, and so the budgets followed. Our media buying habits shift quickly to where it is most effective, and for the last 7 years that has definitively been Facebook and Google. The problem is that the same segmentation that’s creating massive opportunities for brands is causing massive problems for society in general.

We’ve been arguing since 2015 about what should be done about the problem. We know that people are being misled, but who should police the marketplace? In traditional media, the answer was simple: People looked to their news publisher as a source of trust, so it was incumbent on that publisher to vet all content for its authenticity, and ads fell under that umbrella.

In social media, it’s not so simple. The platforms provide access to a network of sources, but how can they also be expected to vet every one of them? The ad model was set up to be self-serve in order to scale and to give access to these powerful tools to anyone with a computer and a credit card.

Jack is proposing that the problem isn’t the way that the networks are running the model. He’s suggesting the problem is with the model itself.

This new decentralized version of social media would operate somewhat like an app store. There would be one set of rules that everyone would build from, then users would be presented with a variety of options. They could choose a different brand of social media news feed, the way that people used to choose which magazine to subscribe to.

Right now, each social media channel must build itself from the ground up, so each network has its own way of linking people together and serving them content, and those things are locked into that network. What if, instead, each user was able to bounce from one algorithm to another, fully aware of the bias that each was built from. In fact, in this scenario, the bias would be a feature rather than a bug. You may sign up for an algorithm built specifically to filter out certain types of content, or to feature others. You may have one that heavily weighted your closest friends and another that focused mostly on expert sources.

The reason to be optimistic about Jack’s Bluesky idea is not that he, or his team, are necessarily going to be able to pull it off. It’s because the current model just isn’t sustainable. Relying on a couple of massive companies to act as our common source of news worked when they were also the authors of that news. When the sources are nearly infinite and the primary function of those companies is to filter, then the only option is to give the users some level of transparency and control over those filters.

Brands will undoubtedly be a big part of whatever the next phase is for social media, and the criteria for taking advantage of that phase-change will be the same as it was the last time around: Clearly identify the value that you offer and the communities that you offer it to, then the tactics are the easy part.